Guardians of the government – the battle to secure the public sector

The recent news that a payroll system used by the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) had been hacked by a “malign actor” underlines the continuing cybersecurity risks facing government departments. In this case, the breach impacted a system managed by an external contractor, resulting in the exposure of names and bank details of armed forces personnel.

But how common are attacks on government networks and the wider public sector supply chain? The Center for Strategic and International Studies publishes a timeline of significant cyber incidents across government agencies, defense and high-tech companies.

They list incidents impacting the governments of the USA, the UK, India, Germany, Indonesia, Taiwan, Canada, the Netherlands, Sweden, Australia, South Korea, Japan and Denmark, among many others. Elsewhere, a study published by Blackberry revealed that the government and public sectors are most frequently targeted by unique malware, representing over 35% of cases in total.

In the US specifically, threat actors have targeted the U.S. State Department, the Department of Justice, the Department of Homeland Security, and the US Armed Forces, among others, in just the last 12 months alone. In one incident, Chinese hackers reportedly stole tens of thousands of emails from U.S. State Department accounts, following a breach of Microsoft’s email platform.

The threat actors

In general, threat actors fall into two main categories: nation-states and cybercriminals. Among the nation-state protagonists, Russia and China are most commonly associated with security incidents and breaches. As part of its invasion of Ukraine, for example, Russia has routinely employed cyber warfare tactics to cause damage and disruption, using cyberspace as “an established and fast-developing domain of conflict”, according to a report by the EU.

The motivation behind these activities varies, with the 2023 Microsoft Digital Defense Report explaining that “After last year’s flurry of high-profile cyber attacks, nation-state cyber actors this year pivoted away from high volume destructive attacks and instead directed the bulk of their activity toward cyber espionage.”

State-sponsored cyber espionage can have a range of objectives, including the theft of military secrets, IP or other sensitive information. In addition, attacks can target personal data that can then be used to coerce victims into acting on behalf of the nation-state.

Nation-state attacks are also motivated by political objectives, which can include influencing public opinion or disrupting elections. This year, for example, over 50 countries (equivalent to half the world’s population) will hold national elections, with governments on high alert to identify and prevent interference.

For cybercriminals, whose motivation is usually financial, government organizations are just one of the sectors they target. Among their most common tactics is using ransomware to extort payment to release encrypted systems or exfiltrate data to sell on the dark web.

The impact

The impact of incidents that reach the public domain varies, with the most high-profile causing major disruption to public sector health organizations.

This includes the UK’s National Health Service, which suffered major disruption during the 2017 ‘wannacry’ ransomware attack, while in March 2021, Ireland’s healthcare system was severely impacted after hackers duped an employee into clicking on a spreadsheet.

More recently, a high-profile attack last year on the Children's Hospital in Toronto was delivered via an affiliate of the LockBit gang using Ransomware-as-a-Service, with patient data and services critical to life being put at risk.

Elsewhere, government departments are subject to ongoing cybersecurity risks, with threat actors testing network defenses, exploiting zero-day vulnerabilities and using complex social engineering strategies to breach security perimeters. While calculating the overall financial impact is difficult, cybercrime as a whole is expected to cost the world $10.5 trillion a year by 2025, according to an industry study.

Delivering proactive protection

To address these varied and concerning challenges, government and regulatory authorities around the world are implementing a growing range of compliance requirements. For example, the National Cross Domain Strategy & Management Office (NCDSMO), which is part of the NSA, is the focal point for U.S. Government cross-domain capabilities and mission needs. Its ‘Raise the Bar’ strategy came into force in 2018 and is designed to improve “cross domain solution security and capabilities from a design, development, assessment, implementation, and use perspective.”

In this context, the secure transfer of data across trust boundaries is vital for government agencies, and Cross-Domain Solutions (CDS) are becoming an important technology choice for enabling the exchange of information between isolated and external networks. However, traditional detection-based antivirus and sandbox solutions fall short of protecting departments against new and existing file-based threats. What’s more, the air-gapped nature of secure networks also makes it difficult to keep antivirus solutions updated, representing an additional security risk.

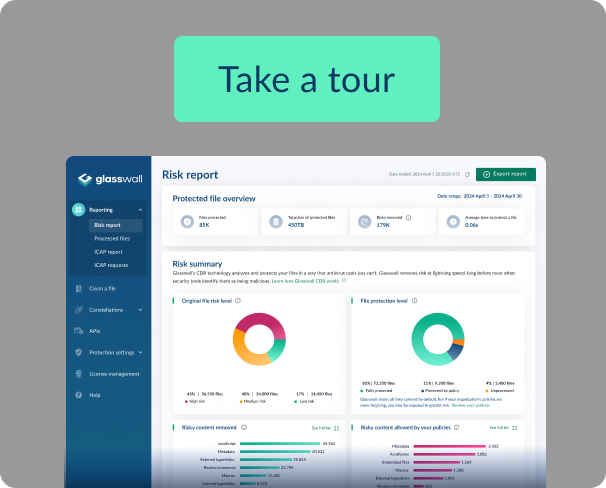

Glasswall Content Disarm and Reconstruction (CDR) adds functionality to CDS, including secure document, image, and media file transfer, data loss prevention, and the ability to transform complex data types into simple/verifiable ones for syntactic and semantic verification. Unlike detection-based solutions, Glasswall CDR is not dependent on antivirus databases or updates to provide knowledge of new threats, making it perfect for air-gapped secure networks where regular patching and updating are difficult.

Our battle-hardened technology is mandated for use as a file filter in Cross Domain Solutions by the NSA and is trusted by the world’s most sophisticated security establishments. It is also recognized as SOC 2 Type II compliant, meaning our reporting and control activities are proven to be secure over the long term.

Glasswall CDR case study: HM Government

A large UK government agency had terabytes of important data on an isolated network which could have contained malicious content. They required urgent access to this data, but the only option available to secure it was to ’sheep dip’ the data – use antivirus and analysis tools to test each file for malware on a separate computer. Understanding that antivirus detection only offers limited protection and not having the time or resources to analyze every file manually, they required a solution that didn’t rely on legacy detection-based methodologies.

A deployment of Glasswall CDR enabled the cleaning and transfer of files from the untrusted to the secure network. Glasswall was able to move fast, working seamlessly with the government agency. Terabytes of secure data were imported into the new environment within days, and the government agency had complete confidence that there was no malicious content in the data due to its zero-trust file protection capabilities.

To learn more about how Glasswall works with government agencies to deliver proactive, zero-trust file protection, contact us.